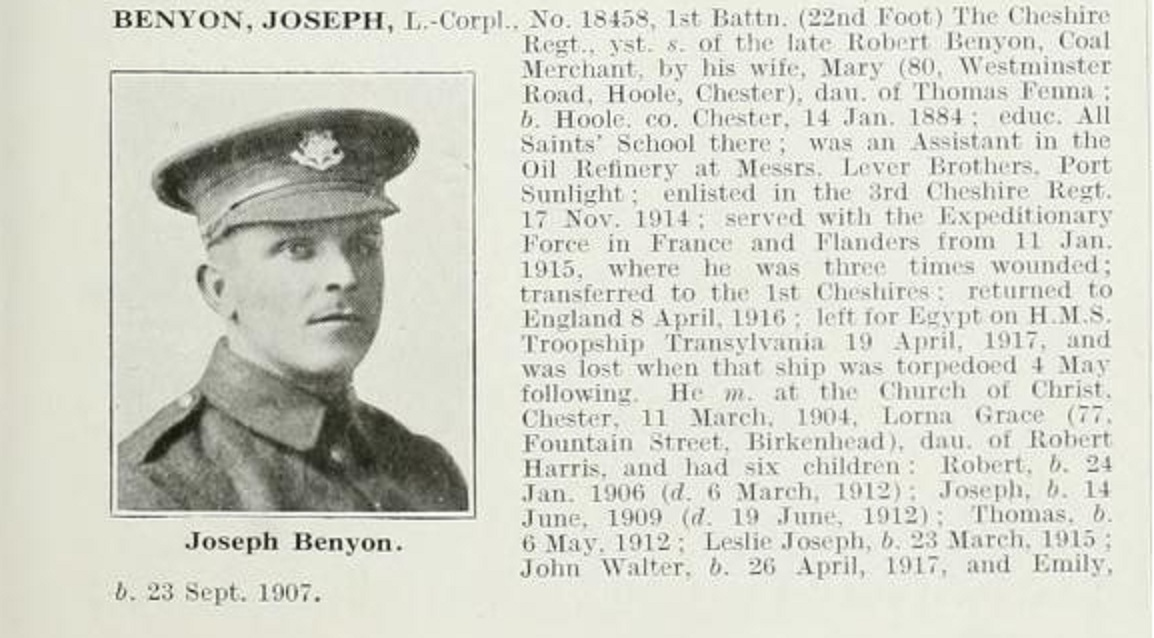

Remembering Private Joseph Benyon

18458 of the 1st Battalion Cheshire Regiment

He died 100 years ago today on 4th May 1917

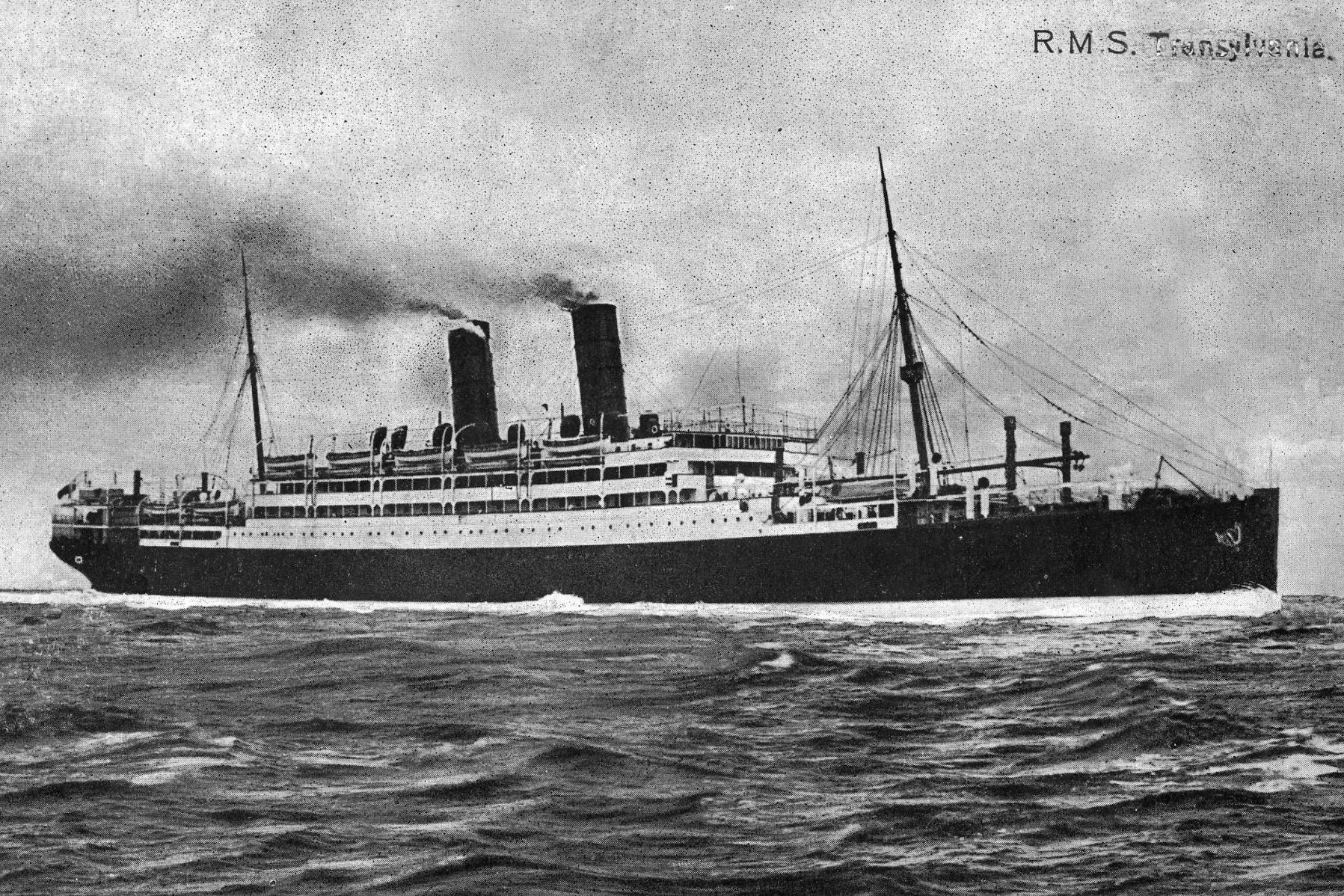

My great Uncle Joe died on 4th May 1917 aged 33 years. Joseph was aboard the troopship “Transylvania” in the Gulf of Genoa near Savona, Italy, when it was torpedoed by a German U-Boat. There were over 3000 army officers, soldiers, nurses and crew aboard the ship which was travelling from Marseilles in France to Alexandria in Egypt. On that tragic day 413 souls were lost.

Joseph was born on 14 January 1884 in Hoole, Chester to Robert and Mary Benyon, (née Fennah). He was the 7th of their 10 children and younger brother to my Grandmother Martha Benyon, (1876-1954). Educated at All Saints’ School in Hoole, he then worked his way to becoming an Assistant in the Oil Refinery at Messrs. Lever Brothers in Port Sunlight. On 17 November 1914 in Birkenhead aged 30, he enlisted into the 3rd Cheshire Regiment.

He married Lorna Grace Harris (1883-1970) at the Church of Christ, Chester, on 11 March 1904. They had six children :

Robert, b: 24 Jan 1906 (d: 6 March 1912);

Emily, b: 23 Sept 1907 (d: 1998);

Joseph, b: 14 June 1909 (d: 19 June 1912);

Thomas, b: 6 May 1912 (d: 1986);

Leslie Joseph, b: 23 March 1915 (d: 2000), and

John Walter, b: 26 April 1917 (d: 1940)*.

Joseph & Lorna with Baby

* John Walter was born just one week before Joseph sailed from Marseilles on the Transylvania, ironically John was killed in action during the evacuation of Dunkirk on 30 May 1940.

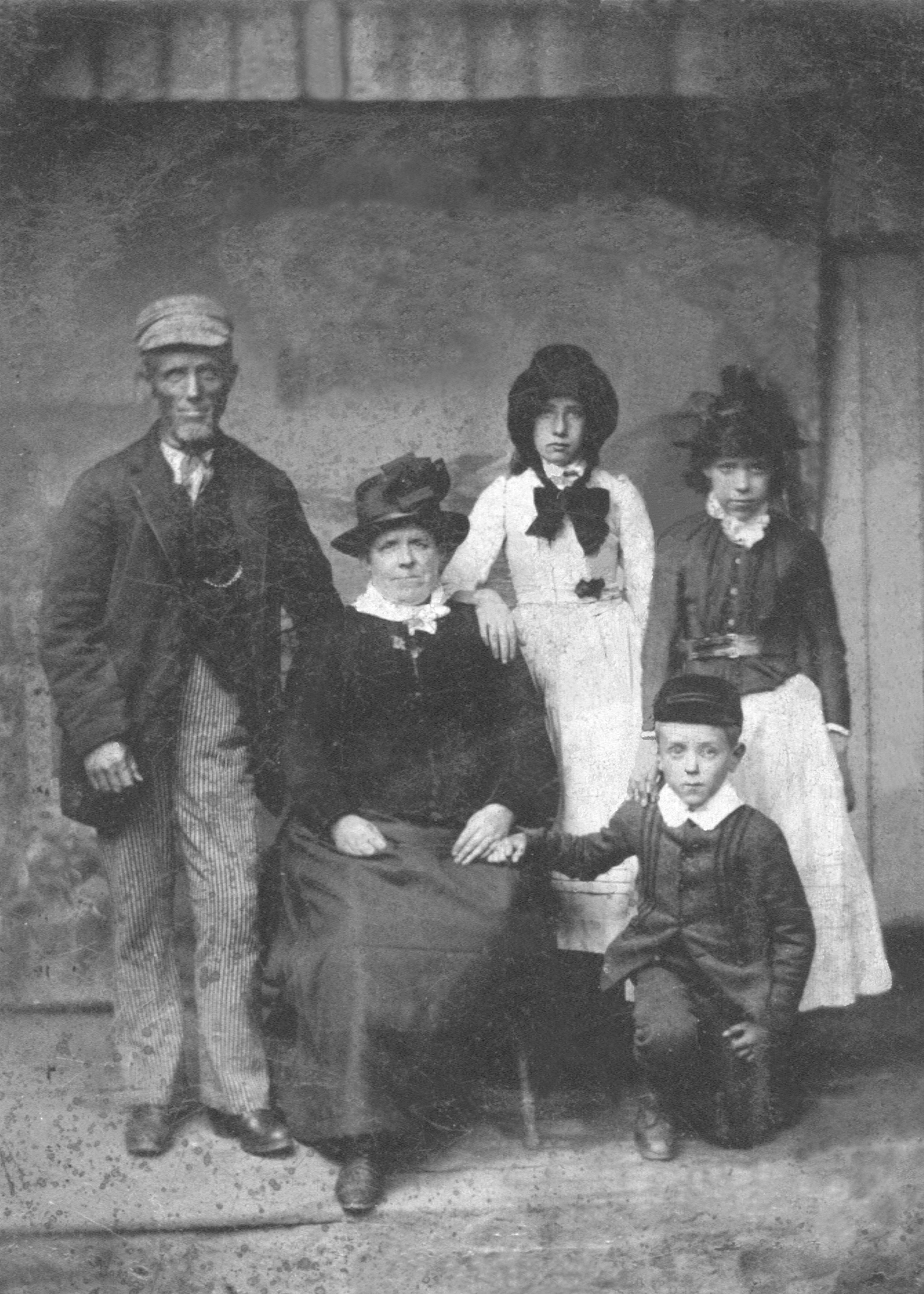

Early Family Years

In the early 1880’s Josephs parents were living in Bishop Street, Hoole, Chester. The 1881 census shows Robert as an unemployed labourer, Robert and Mary at this time had 4 children between 1 and 10 years old living with them. By the time of the 1891 census their fortunes had improved, Robert was now a Coal Dealer and the family had moved to 1 Peploe Street in Hoole (this was later renamed Westminster Road). They now had 8 children living at home with the 3 eldest boys all employed. Joseph was 7 years old and a Scholar.

Family Photograph (Date unknown) – Robert and Mary Benyon.

Probably 3 of their children, boy kneeling might be Joseph.

Jump forward to 1901 and the family had now moved to the more fashionable Hamilton Street in Hoole (number 13). Joseph (now 17), is described as a Coal Carter, possibly working for/alongside his father Robert who is still a Coal Dealer.

- Three years later in 1904 Joseph marries Lorna Grace Harris in Chester.

- January 29th 1906 – Death of Joseph’s father Robert Benyon, aged 63.

- Mary lives on to the grand old age of 99, dying in 1946. She was affectionately know as Granny Benyon in the Hoole area, she had lived there almost all her life.

In the 1911 Census Joseph and Lorna are found to be living at 4 Griffiths Terrace in Hoole, Chester with their 3 children Robert, Emily and Joseph jr. Joseph was now a Coal Carter for the Co-operative Society. Between 1911 and 1914 the family had moved to 77 Fountain Street in Birkenhead. By the outbreak of the first world war in July 1914 Joseph had obtained work at Lever Brothers in Port Sunlight.

War Time

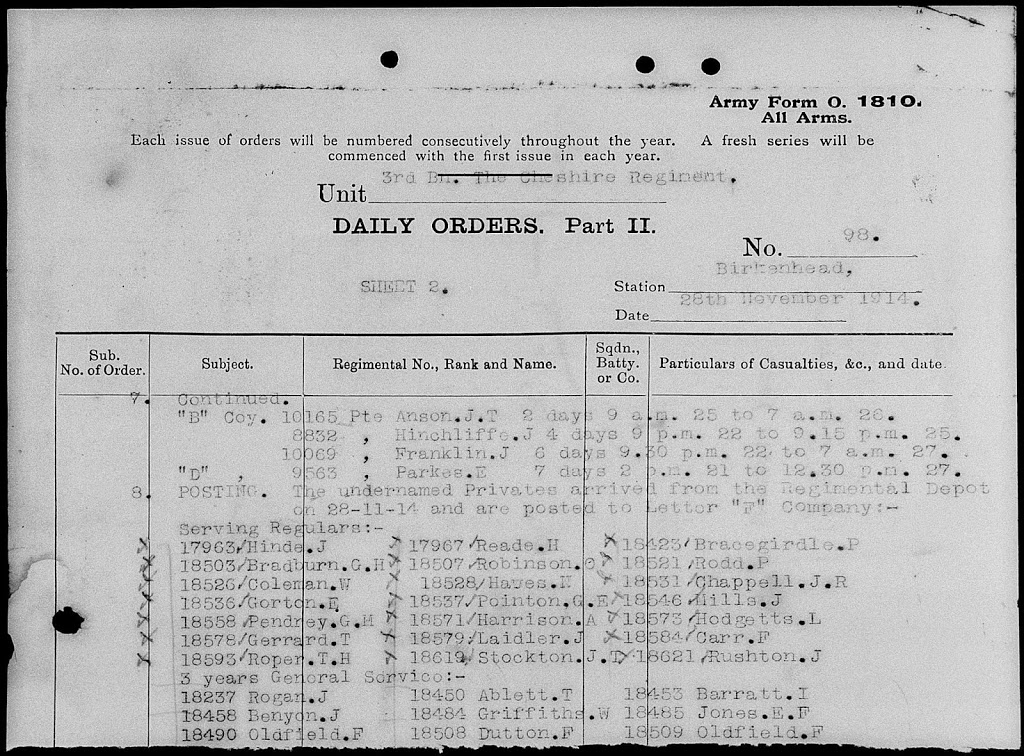

On the 14 November 1914 Joseph enlisted with the 3rd Cheshire Regiment for 3 years general service. Unfortunately no service records survive for Joseph Benyon (confirmed by the Cheshire Military Museum), however it has been possible to reconstruct his possible movements, actions and injuries based on other documentation.

“POSTING. The undernamed Privates arrived from the Regimental Depot

on 28-11-14 and are posted to Letter “F” Company”

Joseph joined the 3rd Training Reserve Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment who were located in Birkenhead. At this time, the battalion was undertaking guard and security duties at the Mersey Dock installations. The Battalion in the early part of the war supplied overseas drafts of trained recruits to the 1st Battalion in France.

On 11 January 1915 (see De Ruvignys Roll of Honour) Joseph appears to have been transferred to the 1st Battalion to serve with the Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders. The 1st Battallion war diaries back this up, as on 20 Jan 1915, it says 24 reinforcements arrived at Bailleul, the Battalion’s current location. Joseph’s Medal Card backs this up showing that he entered the Theatre of War in France on the 11/1/15.

Using the war diary we can now track Joseph’s movements over the next 15 months to the 8th April 1916, whence he was repatriated due to a bomb wound to his left arm. De Ruvignys Roll of Honour (DR) actually states that he was wounded three times, however only one injury seems to have required repatriation.

The war diary entries over this period are very extensive and cover many locations in France and Belgium. It is impossible to include the detail on a day to day basis as they take up 50+ pages of information, some of which is quite horrific. Below is a list of all the places that the Battalion was located throughout this period and is undoubtedly where Joseph was billeted. You should also be aware that the Battalion actually marched from from one location to another! The only train journey was between Godewaersvelde and Corbie.

Bailleul, Wulvergem, Dranoutre, Lindenhoek, Ypres, Ypres Kruisstraat

Vlametinge, Tuileries 8902 Belgium, Dikkebus, Zillebeke, Ouderdom

Reningelst, Godewaersvelde, Corbie, Pont Noyelles, Morlancourt

Fricourt, Meaulte, Sailly-Lorette, Bray, Etinehem, Chipilly, Vaux-en-Amienois

Camps-en-Amienois, Candas 80750 France, Warlus France, Arras, Duisans

To get more detail on the exploits of the 1st Battalion in the period of Joseph’s involvement I would recommend reading pages 33-63 of The History of The Cheshire Regiment in The Great War by Col. Arthur Crookenden.

Wounded

Military Hospitals Admissions and Discharges Register WW1 (Ref MH106/20)

No 42 Casualty Clearing Station.

Lance Corporal (18458) Joseph Benyon, admitted with bomb wound to left arm 8th April 1916. Transferred to other hospital 9th April 1916.

The war diary entry for 8th April 1919 reads:

TRENCHES 2 Coys ARRAS

Bn. releaved the 1st Bedfordshire Regt. in K.2. fire trenches. 8 casualties were caused by aerial torpedo during relief (3 killed)

From this postcard we can assume that Joseph was admitted to Bellahouston Hospital in Glasgow for treatment of the bomb wound.

Bellahouston was a Scottish National Red Cross Hospital – no records of military patients seem to have survived.

On the rear of the postcard someone has written “Reported missing and drowned. May 21st 1917. On Transylvania. L/Cpl Benyon 1st Cheshire Regiment”

When Joseph was admitted to No. 42 Casualty Clearing Station it was temporarily located in Licheux, (between 1st and 19th April 1916). This CCS was normally located in Aubigny, records show that it was located here between Feb 1916 and 25th Aug 1918. CCS No’s 24, 30 & 57 were also located in Aubigny during WW1.

The Casualty Clearing Station was part of the casualty evacuation chain, further back from the front line than the Aid Posts and Field Ambulances. The job of the CCS was to treat a man sufficiently for his return to duty or, in most cases, to enable him to be evacuated to a Base Hospital. It was not a place for a long-term stay. CCS’s were were usually quite large and generally located on or near railway lines, to facilitate movement of casualties from the battlefield and on to the hospitals.

To understand more about the CCS’s I recommend you read this article from a blog post on

This Intrepid Band It is viewed through the eyes of the Matron-in-Chief, Maud McCarthy, on her visits of inspection.

Joseph was repatriated from France on 9th April but must have been back home from Bellahouston Hospital by the end of July 1916 when John Walter was conceived (b:26th April 1917).

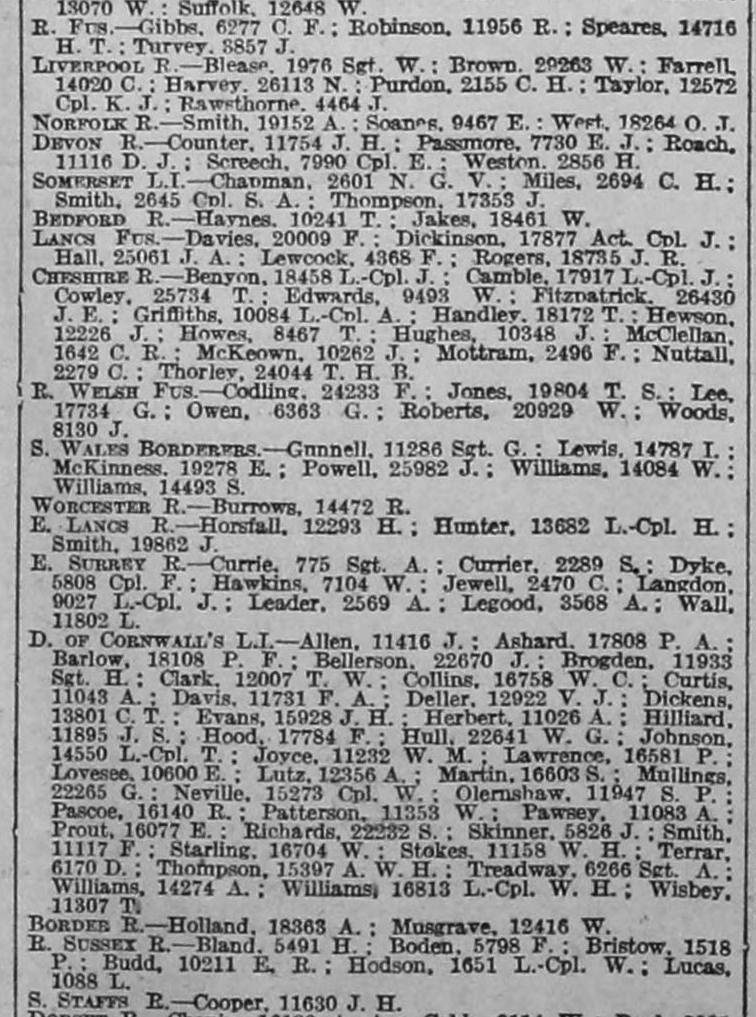

The Cheshire Regiment journal called The Oak Tree dated 15th April – 15th May 1916 records that “18458, L/C. Benyon, J” was wounded. This would indicate that Joseph was wounded just prior to the Somme Offensive which began on the 1/7/16.

The Times Newspaper dated 2nd May 1916 also reports that Lance Corporal J Benyon 18458 had been wounded.

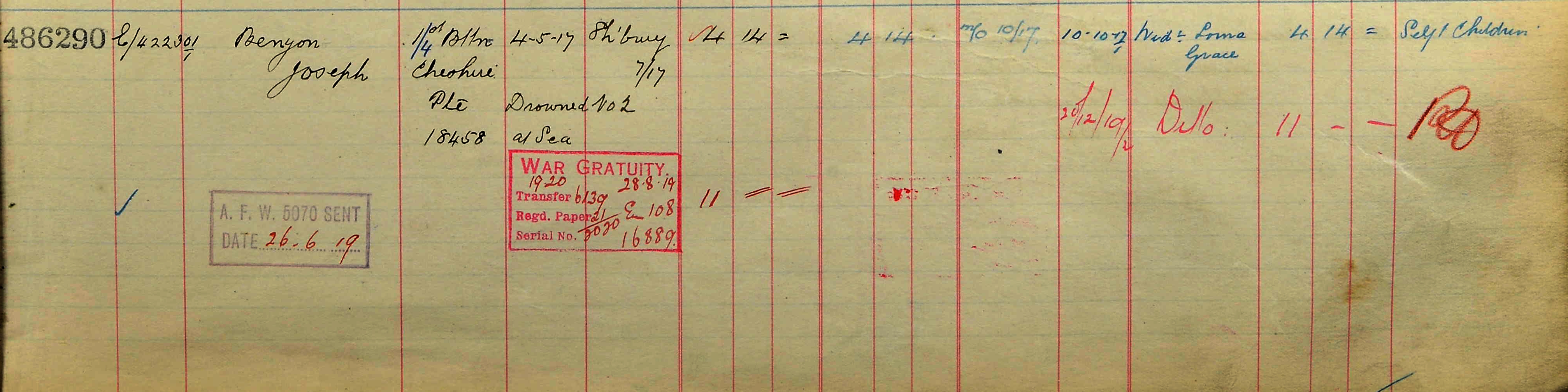

On the casualty list and De Ruvignys Roll of Honour Joseph’s rank is recorded as Lance Corporal, but details held by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and the War Medal Indexes (see Medal Card above) record his rank as being that of Private. The rank of Lance Corporal was a temporary appointment, it was given to a Private who showed initiative and looked like being a good prospect for becoming an N.C.O. It was a temporary position and at any time the soldier found that he did not like the responsibility of rank, he could make this clear to his Commanding Officer and return to being a private without this decision being held against him.

From the War Graves Registration Report we can see that after recovering from his wounds Joseph returned to the 3rd Training Reserve Battalion. By this time the 3rd Battalion had gone to new hutments in Bidston, Wirral, retaining Gamlins Furniture Depot for Headquarters,stores,recruits and the necessary training staff. Besides recruits they also comprised convalescent men and men awaiting discharge. Joseph was undoubtedly one of the men convalescing, he would later be sent on his fateful journey to join the 4th Territorial Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment who were serving in Palestine.

RMS Transylvania

After his recovery from the bomb wound, Joseph must have returned to the 3rd Battalion waiting for a suitable posting back to the theatre of war. He was eventually posted to Alexandria in Egypt on route to Palestine where a weakened 4th Battalion were in need of some reinforcements. Whether he was at home for the birth of his last child (John Walter) on the 26th April 1917, is difficult to say, as 7 days later he would have boarded the Transylvania in Marseilles.

They left the harbour at Marseilles on the evening (about 8pm) of the 3rd May on route to Salonica, (modern day Thessalonica in Greece where the nurses were bound) and then to Alexandria. Soon after leaving they were joined by 2 Japanese destroyer’s, the Matsu and the Sakaki, who were to escort them to the final destination. The Transylvania was originally designed to carry 1,379 passengers but for military purposes the Admiralty fixed her capacity at 200 officers and 2,860 men, besides crew. She was carrying nearly this number when she left Marseille with over 3000 army personnel, 60 Red Cross nurses and a ship’s crew.

Conditions on-board ship must have been cramped and difficult. In his book “Hell in the Holy Land” David R. Woodward describes how one regular soldier bitterly resented the privileged position of the officers………..

On the upper decks he observed “a luxurious smoking lounge, comfort

in every corner,” and a dining saloon with “white linen, shining cutlery

and glass—dining chairs around the table in real hotel style.” The officers’

sleeping accommodations with baths included reminded him of

what “I once enjoyed.” When he descended to his quarters,

the first thing that strikes one is the smell of mules assailing the nostrils,

combined with the unholy smell which rises from imperfectly ventilated

spaces from between decks. Side by side with the mules and in the remaining

stalls many men have their quarters, taking their food there and many of them

sleeping there. Lower again on the mess deck are the remainder of the men.

Sister Hayward, a nurse travelling to Salonica, notes in her diary that “lifeboat drill was a farce”, the nurses were told to wear their lifebelts continuously. British soldiers began their voyage to Egypt with drills to deal with the U-boat threat, but according to several accounts, they were poorly organised and a serious omission was that no one was instructed on how to lower a lifeboat!

At 10 a.m. on the 4th the Transylvania was struck in the port engine room by a torpedo from a submarine. At the time the ship was on a zig zag course at a speed of 14 knots, being two and a half miles S. of Cape Vado, Gulf of Genoa. She at once headed for the land two miles distant, while the Matsu came alongside to take off the troops, the Sakaki meanwhile steaming around to keep the submarine submerged. In fact the torpedo had struck the bunkers near the port engine room, it had been launched from 300 yards away by the German U-boat U-63 under the command of Otto Schultze.

From an article in The Times newspaper (26 May 1917). John May, second cook on Board explains what happen next:-

There was a terrific explosion and many of the men must have been killed by it. At the time the troops on board, who included men from Liverpool and Birkenhead, were on parade on deck. They behaved splendidly, and there was no panic whatever. The crew had a clear way to the deck from below, and as they came up they saw the soldiers standing in line five deep. Sixty-six nurses were also on board and showed splendid self-possession, and when after the cry of “Women first was raised the nurses were being lowered to the boats, one of the women called out, “Give us a song boys.” To this the soldiers at once responded, singing, first, “Tipperary,” and then, with a touch of grim humour, “Take me back to Dear Old Blighty.”

It was obvious that the vessel was doomed. Several destroyer raced along to the rescue, and while they were thus engaged and while a boatload was being lowered a second torpedo struck. Mr. May, finding the Transylvania heavily listing, went over the side and was pulled into the boat. Nearly all the boats were half full of water, and it was impossible to row ashore owing to the heavy sea. The destroyers did magnificent rescue work, and every available part of the decks was covered with nurses and soldiers, many of the men having to sit astride the guns. The destroyers kept cruising round until help came from the shore four hours afterwards, but the Transylvania went down in 50 minutes.

From Hell in the Holy Land – R. G. Frost, a driver for No. 905 Company in the Motor Transport, recalled:-

….the lifeboats were in shocking order, some of them turning upside-down and hurling the occupants into the sea. None of the men knew how to lower them as there had been no lifeboat drill and one end of a boat would go down while the other stuck. One boat was lowered on top of another and, it is thought, killed many of the underneath boats companions. In several cases the wrong ropes were cut, and the boats fell into the sea or hung suspended by one end. Frost also observed that “that most of those which were lowered safely, either had the caulks out or were in an unseaworthy state”

From a letter by Private Samuel Kidger of the Northumberland Fusiliers:-

A JTBD [Japanese torpedo boat destroyer] had just drew alongside and was taking men off when I saw a second torpedo coming through the water and it was worse than the first and then the order was “Every Man Overboard”. It was awful, we could not launch no more boats, the Rafts we threw overboard to the men in the water. I was on the point of jumping in also. I had take my boots and puttees off when I saw a second JTBD coming alongside and I jumped on to her as she was passing us. I might say that there was hundreds saved like that, all honour to the Japs who are brave men. I also saw men fall between both ships and were crushed to death. I shall never forget it. I got off 10 minutes before she sank.

From an amazing 12 page letter written by Billy Bowden of the Cheshire Regiment. He gives graphic recollections leading up to, during, and after the event:-

The torpedo had destroyed lifeboats on one side of the ship, there were 4 lifeboats that were too fast to be lowered and had to be left hanging on the davits, the water was thick with men screaming and shouting as they struggled for dear life. Everything that could float was thrown over board. There were about 5 or 6 boats full of survivors pulling for the shore. One of the Japanese boats came along side the Transylvania to take off soldiers and tied up with ropes, then cries rose up from between the ships – there were two rafts laden with about 20 men – it was a matter of sacrificing a few lives to save hundreds. The Japanese boat filled up and could take no more men – there were hundreds still on the decks of the doomed vessel. In 20 minutes we could see her gradually sinking – her bow dipped under- the stern was upright – and then she finally disappeared.

Having survived the Transylvania sinking Private William Bowden 265933 of the Cheshire 1st/6th Battalion (age 30), was killed in action a few months later near Ypres. He is remembered on Panel 19 – 22 of the Menin Gate Memorial.

The Rescue and Funeral

The Matsu came alongside and began to take troops on board, while the Sakaki circled to force the submarine to remain submerged. The men and nurses were told that they had at least 3 hours before the ship would sink, however twenty minutes later, a second torpedo was seen heading straight for the Matsu, but it managed to manoeuvre out of harms way by going astern at full speed. Instead, the torpedo struck the Transylvania, a second blow that sank the ship very quickly, less than an hour having elapsed since she was first hit.

Despite the mayhem regarding the launch of ill equipped lifeboats and rafts into a heavy sea by soldiers with no experience, it was probably thanks to the two Japanese destroyers, the Italian destroyers Corazziere and Garibaldi,the two harbor tugs the Savona and America II and four fishing boats from Noli, that there was not even more loss of life.

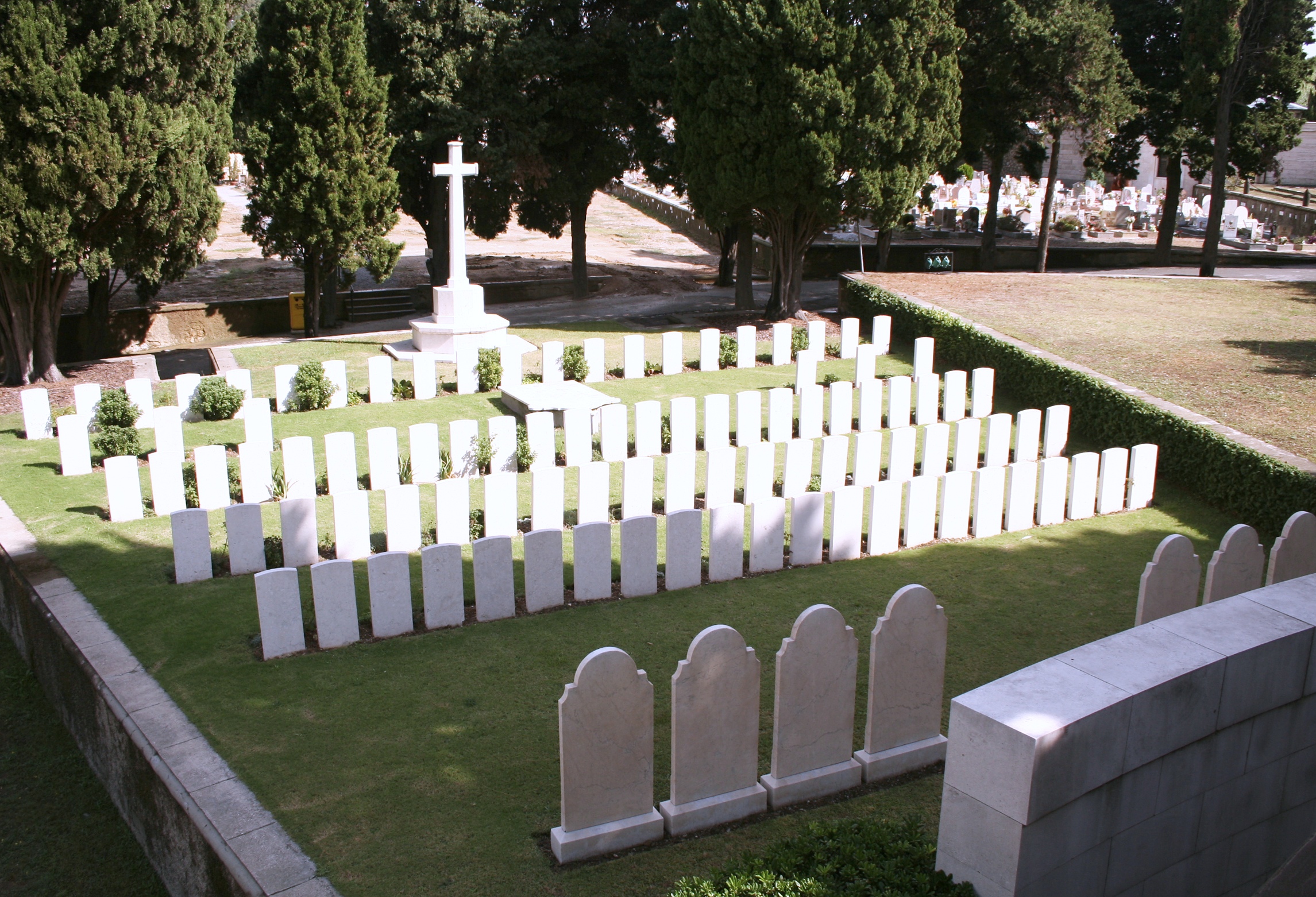

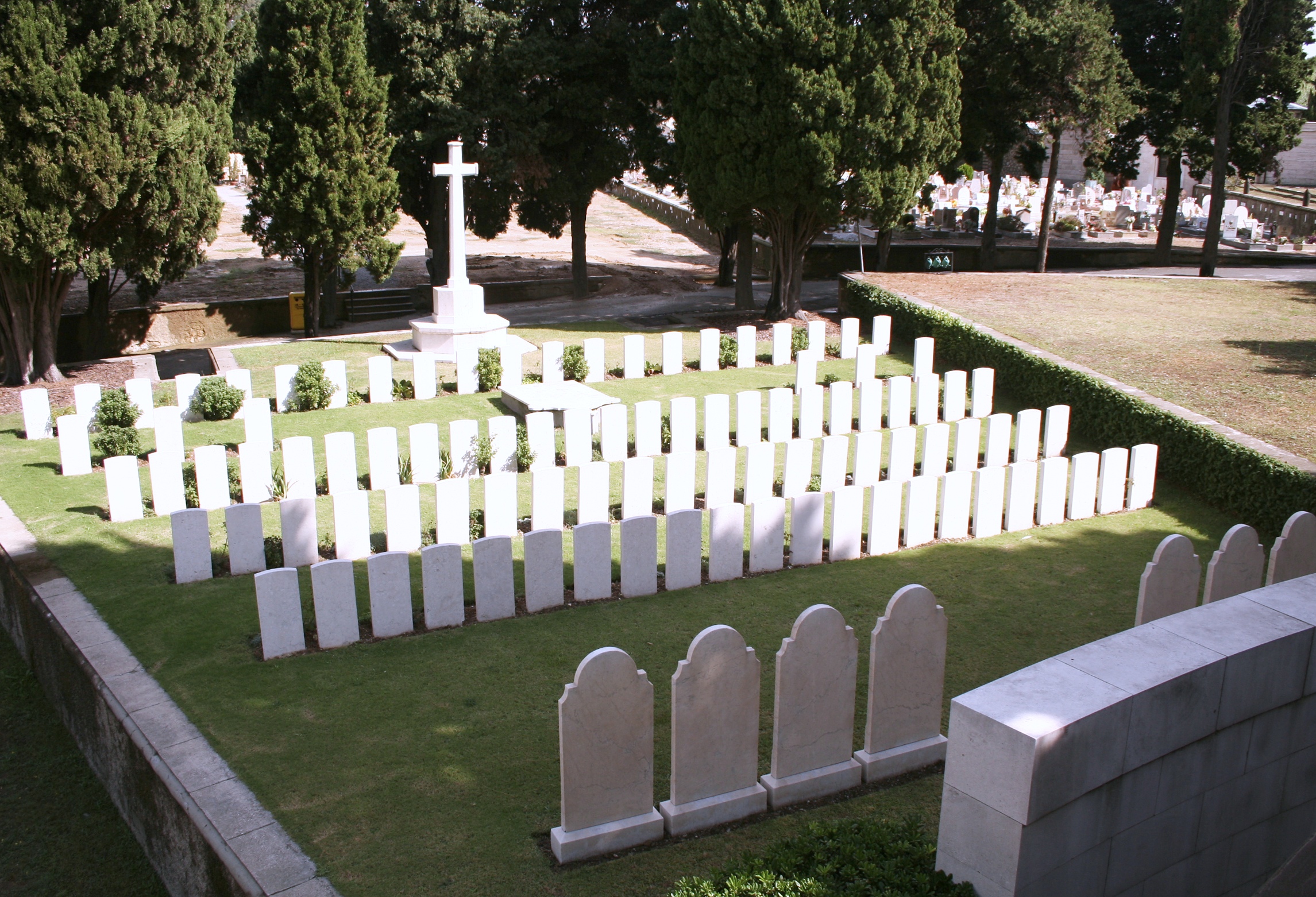

Savona Town Cemetery

Savona Town Cemetery

Twelve crew members, 29 army officers and 373 soldiers lost their lives. Many of the bodies of the victims were recovered from the sea and were buried in Italy, France, Monaco and Spain. Eighty-three were buried at Savona Town Cemetery, which also contains the Savona Memorial to the 275 victims whose have no grave.

It is unknown how Joseph died. Could he swim, was he wearing a life jacket, did he make it to one of the boats or rafts,or was he washed off a boat or raft by the high seas?

It is most likely that he drowned. We will never know, he was one of the 83 victims who were buried in the town cemetery.

From the Commonwealth War Graves Commission Register of Graves we know that Joseph was buried in Plot A12.

Transcription from said register:

BENYON, Pte. Joseph, 18458. 1st/4th Bn. Cheshire Regt. Drowned as a result of an attack by an enemy submarine 4th May, 1917. Age 33. Husband of Lorna Grace Benyon, of 26, Upper Parliament St., Liverpool. Born at Chester. A. 12.

The mass funeral took place on Sunday 6th May. In total there were 13 members of the Cheshire Regiment who lost their lives. Joseph was buried along with 4 other comrades:

Pte. Charles Russell Harris, Pte. Charles Littlemore, Pte. Alfred Turner and Pte. P. Wagg. Seven others are recorded on the Memorial: Pte. Tom Austin, Pte. John Arthur Burgess, Sgt. Ernest Hardstaff, Pte. James Hargreaves, Pte Robert Jacklin, Pte. John Henry Nicholson and Pte. Thomas Povey. Buried in Marzargues War Cemetery in Marseilles is Pte. E.H. Townhill.

Funeral Procession, Savona

Post War

Following Joseph’s death, his widow Lorna Grace would have received “Soldier’s Effects”, which is the money owed to soldiers of the British Army who died in service. The Soldier’s Effects records are a set of registers which were created to account for the settlement of a man’s estate upon his death. These registers show settlement of a man’s wages but more importantly they show the amount of war gratuity which was paid.

Each soldier travelling overseas during the Great War had a Medal Index Card created by the War Office, post war the cards were used to establish a soldiers Medal Entitlement. The card for Joseph (see above top) records that he that he landed in France on the 11 Jan 1915 and was entitled to three campaign medals, which were The 1914-15 Star, The British War Medal, and The Allied Victory Medal.

In 1922 The Marquis De Ruvigny published a Roll of Honour 1914-1919. The collection contains biographies of over 26,000 casualties of the Great War. Casualties include men (both officers and ranks) from the British Army, Navy, and Air Force. 7,000 of the biographies include photographs. If the family of a casualty could provide further background and additional details, then this information was included in the biography as well, sometimes resulting in very detailed biographies. We are lucky that Joseph’s family contributed to this. The photo used in De Ruvigny’s is adapted from our family photograph at the top of this blog post.

Joseph is commemorated on the Hoole War Memorial which stands on the north side of Hoole Road. The memorial was unveiled by Lt-Gen. Sir H.Beauvoir de l’Isle and dedicated by the Bishop of Chester, on Easter Sunday afternoon, 1923.

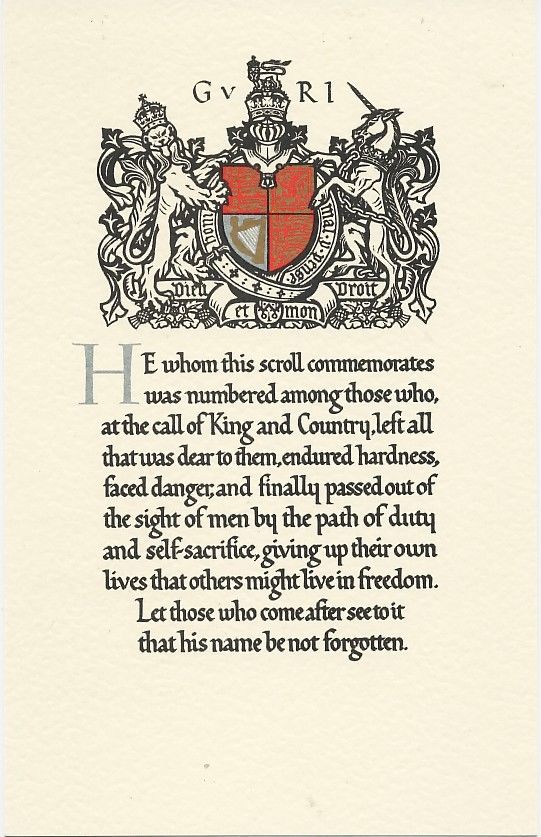

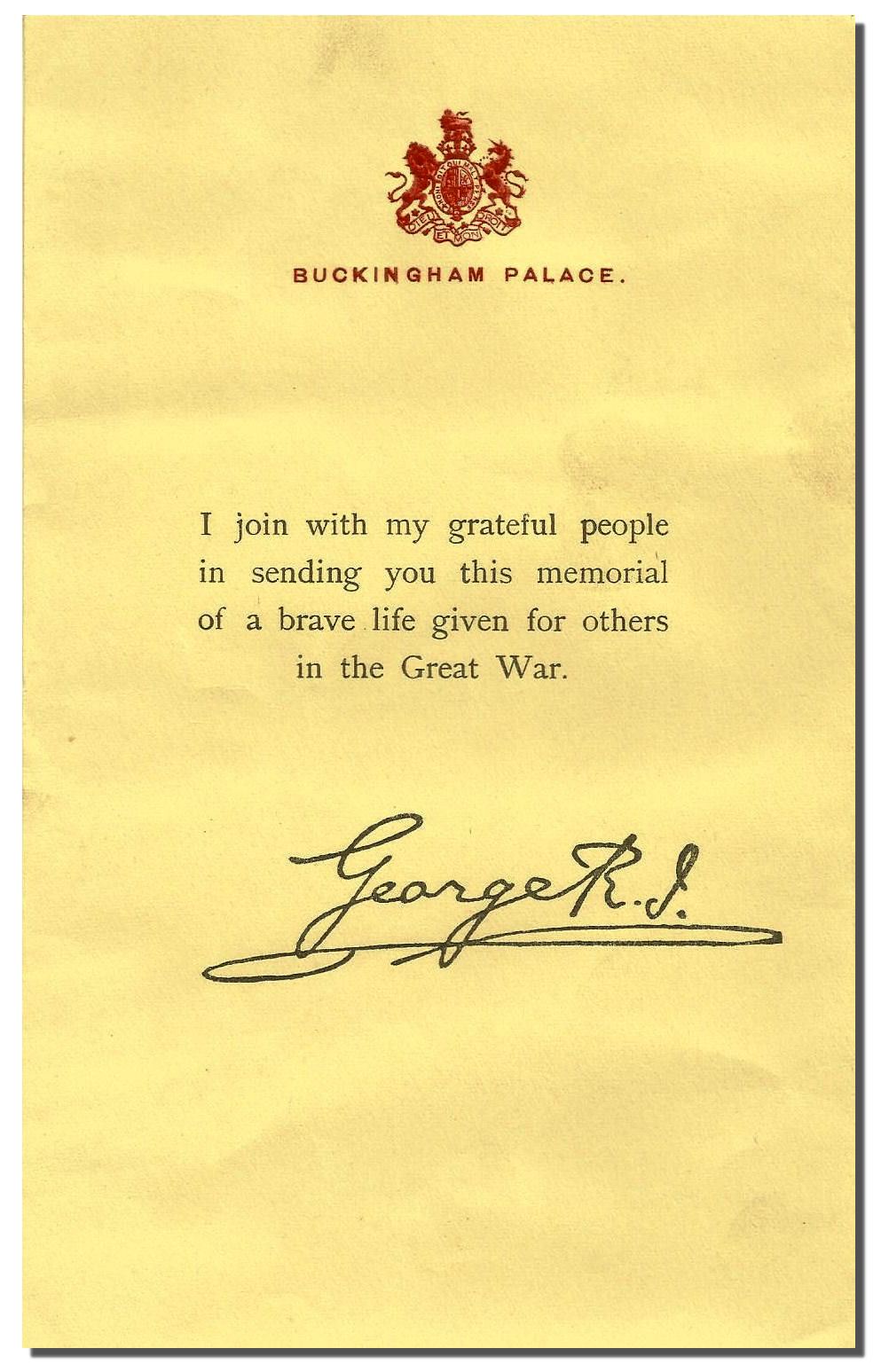

The family would have received a Memorial Plaque (about 5″ in diameter) and Scroll, together with the King’s message. They were issued after the First World War to the next-of-kin of all British and Empire service personnel who were killed as a result of the war. The plaques (which could be described as large plaquettes) were made of bronze, and hence popularly known as the “Dead Man’s Penny” They were posted out separately, typically in 1919 and 1920, and a ‘King’s message’ was enclosed with both, containing a facsimile signature of the King.

Located in 2011

In October 2011, the remains of the Transylvania ship were discovered near the Ligurian coast. For years, the Carabinieri had been examining eye witness reports, trying to determine the location of the disaster. Diver units within the Carabinieri of Genoa finally discovered the shipwreck at a depth of 630 metres with the help of a special robot; it was 2 miles from the Island of Bergeggi. It was able to reveal that the ship had dramatically split into two parts, now laying 150 metres apart on the seabed.

Oral History

Listen here to William Walter Edwards talking in 1987 to the Imperial War Museum about his memories of the sinking of the Transylvania.

William Walter Edwards was a British NCO who served as driver with 14th Motor Ambulance Convoy, Army Service Corp on Western Front, 1915-1916; served with 905 Motor Transport Coy, Army Service Corps in Egypt and Palestine, 1916-1919.

Recollections of sinking of SS Transylvania in Mediterranean, 4/May/1917: description of journey to Marseilles and embarkation aboard SS Transylvania, 5/1917; description of ship and accommodation; question of lifesaving drill; memory of first torpedo striking ship and question of saving nurses first; problem of launching lifeboats; role of escorting Japanese destroyers in rescue; memory of second torpedo striking ship and jumping aboard Japanese destroyer; memory of approaching Italian coastline; question of confusion and behaviour of crew and captain; casualties and loss of property; description of jumping aboard Japanese destroyer and opinion of Japanese crew; memory of SS Transylvania sinking; question of accuracy of casualty figures; memory of arrival at Savona, Italy and help from Italian civilians.

Sources

- A great many thanks go to Geoffrey J Crump, Honorary Researcher at Cheshire Military Museum, The Castle, Chester; who provided me with the information to enable further research into Joseph’s military history and movements.

- Census returns 1891-1911 – www.findmypast.co.uk

- Cheshire Regiment 1st Battalion War Diaries – Jan 1915 to May 1916

- The History of The Cheshire Regiment in The Great War by Col. Arthur Crookenden

- The Casualty Clearing Station – http://greatwarnurses.blogspot.co.uk/2007/02/casualty-clearing-station.html

- CCS Locations – http://1914-1918.net/ccs.htm

- Military Hospitals Admissions and Discharge Registers WW1 – www.forces-war.records.co.uk

- “Loss Of British Troopship.” Times [London, England] 25 May 1917: The Times Digital Archive.

- British Newspapers – www.findmypast.co.uk

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission – www.cwgc.org

- The Dictionary of Disasters At Sea (Hocking/Lloyds)

- Hell in the Holy Land by David R. Woodward

- Jessie Clementia Hayward describing her adventures as a nurse on board the troop ship ‘Transylvania’, 1917 (Norfolk Record Office – MC 2127/1, 441X7)

- Memories of a doctor aboard SS Transylvania – http://1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums/index.php?/topic/199016-ss-transylvania/

- Letter written by William Bowden, who served with Cheshire Regiment – http://www.newbattleatwar.com/hmttransylvania.htm

- A Soldiers Memories – http://www.nottinghampost.com/got-10-minutes-sank/story-20822448-detail/story.html

- De Ruvigny Roll of Honour – www.ancestry.co.uk

- History of SS Transylvania – http://www.azionemare.org/en/transylvania.php

- Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Transylvania_(1914)

- Old Savonia- https://www.facebook.com/vecchiasavona/posts/611723532301476

- Transylvania Historical Society – https://www.facebook.com/Transylvania-Historical-Society-1185942381425101/

- 100th Anniversary Rememberence – http://www.affondamentodeltransylvania.it/

- Imperial War Museum, Oral History- http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80009538

- Family photographs from my private collection.